I’m working through Chapter 4, “Confronting Vietnam, 1965-1975,” for my dissertation, “Partisans of the Old Republic.” Among the historical inquiries animating this chapter is how the Vietnam War impacted American conservatism. Now, this question has yielded some great scholarship. However, earlier work is primarily concerned with the emerging New Right, not the decline of the more noninterventionist, and largely Midwestern Old Right.

While I’ve previously broached this topic here on this blog, I recently ran into a primary source that got me thinking about this decline. Libertarian activist Leonard Liggio provided an analysis of the 1966 midterm elections for “Vietnam News Service: Of the National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam.” In it, he notes that the electoral results could presage a swing towards foreign policy restraint, as had happened in the wake of the Korean War.

Liggio first cautioned the reader that he felt that the results “will not cause a change in the Johnson Administration’s foreign policy.” However, he later noted that the GOP, especially in the Midwest, that “traditional stronghold of isolationism and anti-imperialism,” picked up a number of seats. Liggio’s analysis was tinged with cautious optimism that perhaps the Republican Party’s noninterventionist wing would reassert itself in light of the horror in Vietnam.

For the noninterventionist movement, tragically, he was wrong. As I’ve talked about elsewhere on this blog, the new generation of Republican politicians was considerably more inclined towards interventionism, regardless of region or ideology. Rather than serving as a rebirth of Rightwing noninterventionism, Vietnam heralded its death…at least politically.

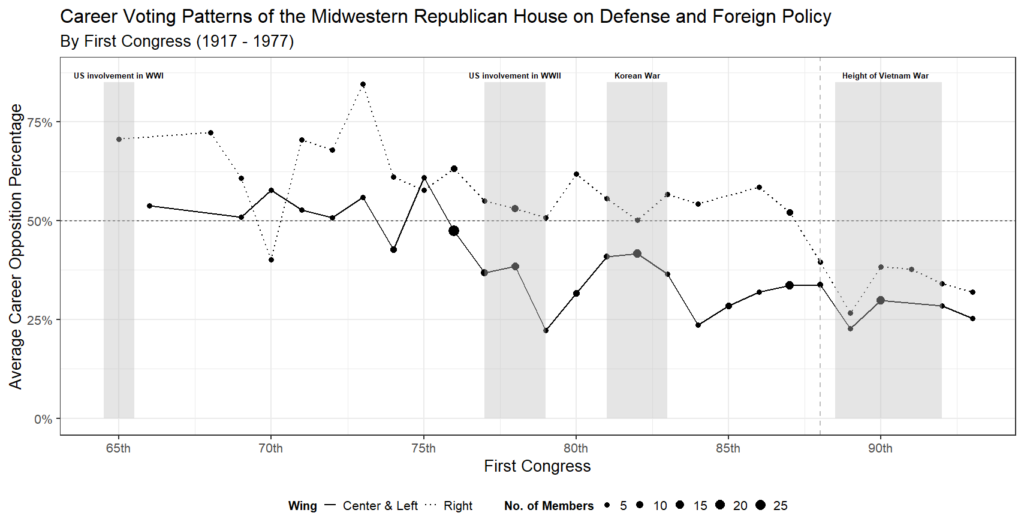

Of the 20 Midwestern Republicans who began their careers in the 90th Congress (as a result of the 1966 midterms), none would crack the 50% mark for foreign policy opposition throughout their congressional careers. As a cohort, these 20 Republicans averaged a mere 31% of opposition throughout their careers, which was actually lower (34%)than that of the other 38 from elsewhere in the U.S. who began their careers in the 90th Congress.

Perhaps unbeknownst to Liggio, the Republican Midwest was already undergrowing a political transformation visa vie its foreign policy worldviews. As a body, new Midwestern Republicans had not averaged a career opposition percentage over 50% since the 87th Congress (1960 general elections, see figure 1). The last Midwestern Republicans to begin their careers in 1960 were Robert T. McLoskey (IL-19) and Pete Abele (OH-10), who served only one term. While popular noninterventionist incumbents would serve throughout the 1960s, none would begin their careers in the decade. This has posed an interesting dichotomy that I am still trying to unpack.

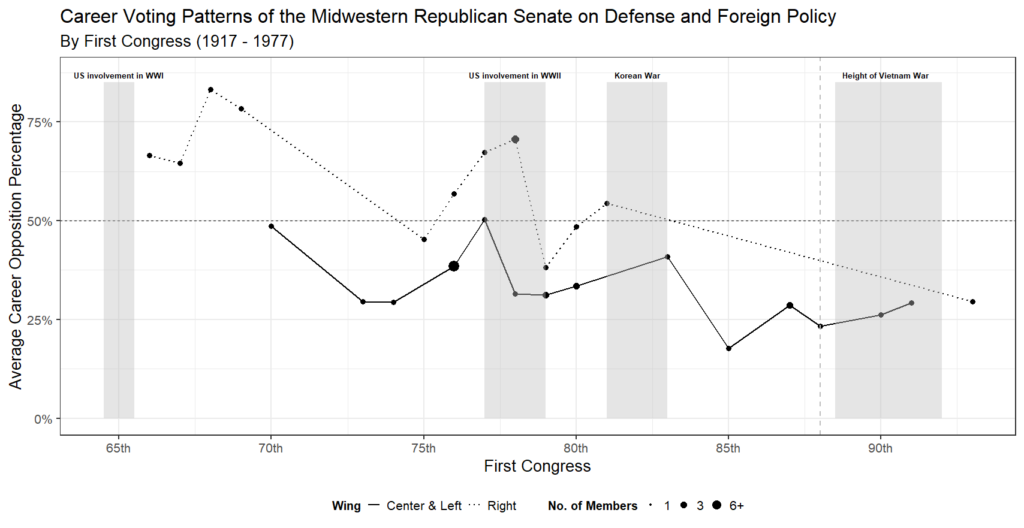

The decline of the House is interesting when juxtaposed with that of the Senate. Republican Midwestern Senators, as a body, shed their noninterventionism faster than colleagues in the House. This is of note because, on the eve of World War II, the Republican Senators from the Midwest were some of the most strident figures in the “isolationist” stable. However, with the exception of two gubernatorial appointments, Midwestern Republicans sent their last noninterventionist to the Senate in Andrew Frank Schoeppel in 1949. Again, some Senate incumbents continued to serve through the 1950s, but new members would not appear through the same period (figure 2).

Liggio was incorrect in his hypothesis. Somehow the tradition of Midwestern noninterventionism died. The data suggest that it was a long, beleaguered, and contextual end. The electoral viability of noninterventionist incumbents, juxtaposed with the inability to create new members, poses a historical quandary, which I am excited to answer.