There is a surprising lack of scholarship on Midwestern conservatism before World War II. What has been written by historians and political scientists is largely concerned with how the region fits into the ascendence of New Right. Examples include The Conservative Heartland: A Political History of the Postwar American Midwest. Conversely, there seems to be an endless body of work have been written on the “Southern Strategy,” its causes, and its impact upon the realignment of Republican conservatism in particular and American politics in general.

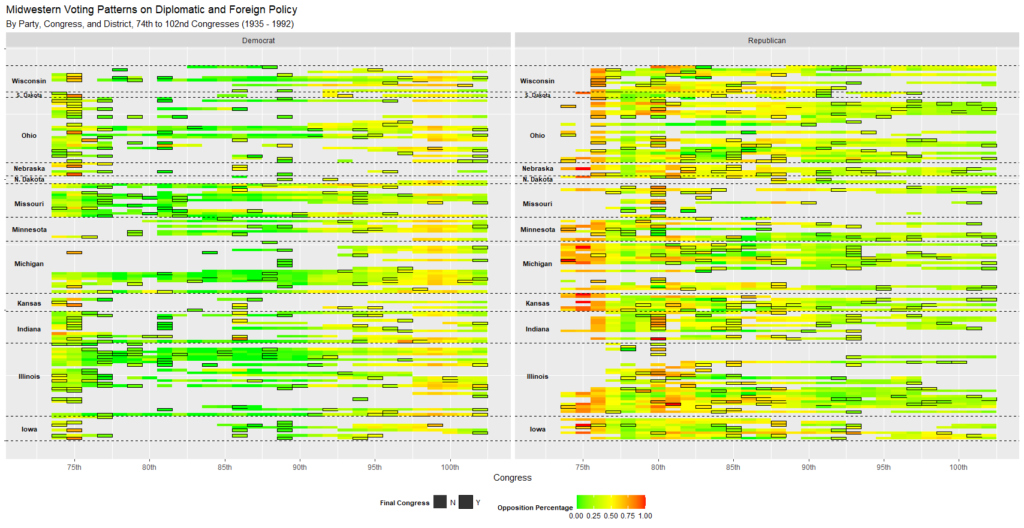

Before World War II, the Midwest was a basion of noninterventionism, both conservative and progressive. Leading noninterventionist political figures and organizations like the America First Committee were active within the region. Opposition was assertive within rural, conservative, and Republican locations.

The rural Midwest served as the backbone of a political faction later known as “the Old Right.” The Old Right was an assortment of fervent anti-New Dealers, trade protectionists, nativists, and noninterventionists. Their political theories were rooted in the region’s history with the Jeffersonian wing of the GOP and were amplified by World War I and the New Deal.

The Old Right opposed to, at least in theory, to everything big: big government; big armies, big labor; big business; and big banks. They embraced romantic notions of American exceptionalism and scorned Europe as a land of iniquity. The Old World represented the worst of all political and cultural outcomes: monarchism; imperialism; corporatism; and socialism. These core beliefs translated into foreign policy positions that opposed entangling alliances, government-directed foreign investment, and large standing armies. Additionally, they advocated for restraining U.S. political influence to the Western Hemisphere.

Despite their prominence within the Republican right, they suffered a rapid decline within the party. The Midwestern right was eventually surpassed by the South, West, and Southwest (collectively known as the Sunbelt) as the center of Republican conservatism. Unlike the rural Midwest, the Sunbelt (aka “the Gunbelt”) was firmly integrated into America’s Cold War economy.

The collapse of the (primarily) Midwestern Republican right remains a criminally understudied aspect of American political history. This decline is interesting to me as the rural Midwest was a basion of noninterventionism before World War II. Pockets of noninterventionism remained well into the Cold War before finally withering away under causes that I’ve yet to grasp fully.

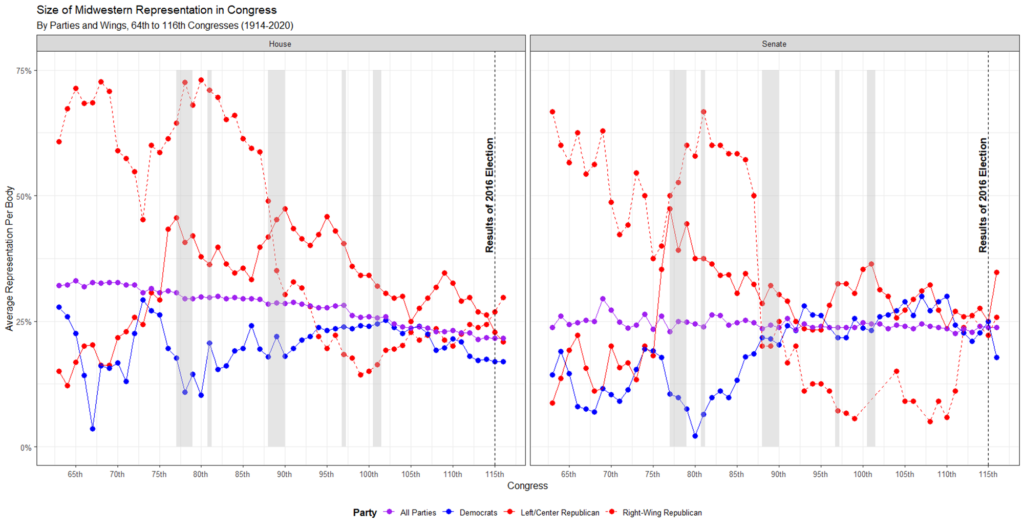

What was the source of this decline? An obvious answer would be the Midwest’s steady population exodus in the post-war period. A population decline could have led to an erosion of national political power, especially in the House. However, this presents an insufficient explanation. When comparing the relative rates of decline between all parties and the various components of the GOP, when can see that the Republican right’s relative size within the Midwest fell considerably faster than the Midwest’s overall representation. Additionally, similar rates of decline also occurred between the Midwestern right’s proportion in the House and the Senate, despite the latter being fixed to two persons per state.

Another obvious answer might lay in election losses as seats changed between Republicans and Democrats. During the high Cold War, the Democratic party was virtually in lockstep with the Cold War consensus. A mass change from the GOP to the Dems would have resulted in an erasure of the Midwest’s distinct noninterventionist political culture, or at least that culture’s representation in the federal government. Looking at the trends, there is undoubtedly something to his hypothesis. The Democrats made significant Midwestern gains between the 80th and 88th congresses (1947 – 1965), particularly in Senate. With the end of the Cold War (102nd Congress, 1991), the center of the GOP and the Democratic party enjoyed similar representation rates in the Senate, with the Republican right firmly in the cellar. While the Midwest still hosted some right-wing Republicans in the House upon the end of the Cold War, they were nowhere nearly as prominent as during previous iterations of the GOP

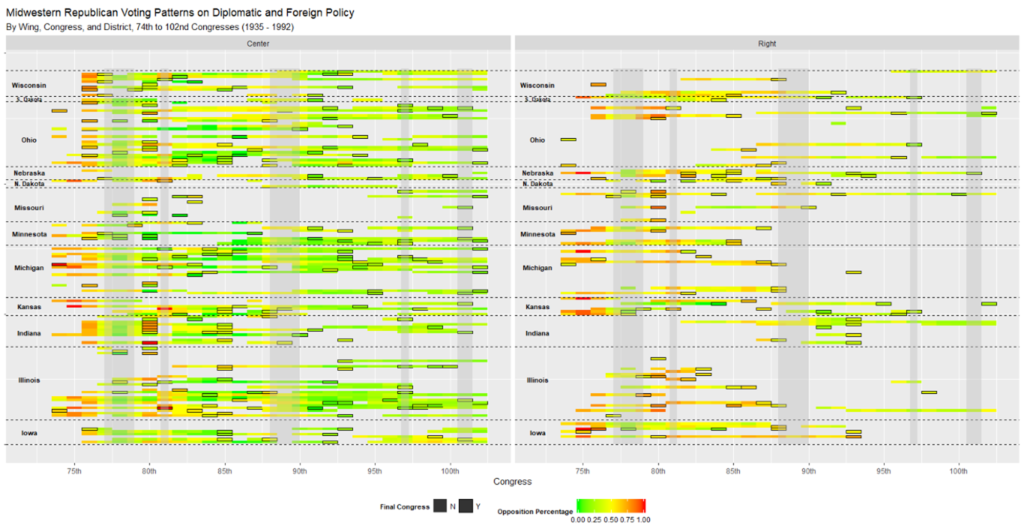

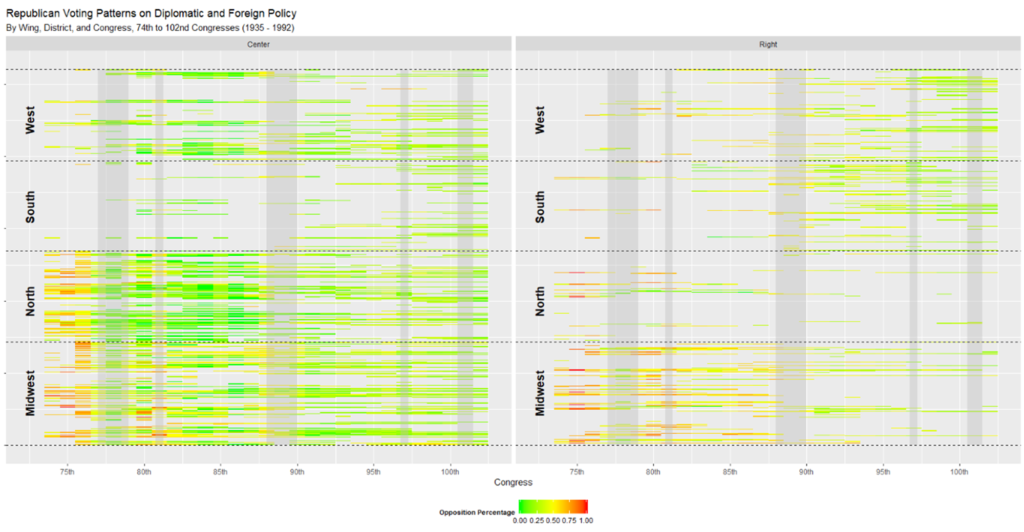

When comparing the electoral fortunes between the GOP’s two primary ideological cohorts, the center, and the right, the former faired considerably better over time. It would appear that the Midwest tacked to the political center. There was also clearly a change in noninterventionism within the Midwestern right (such as it was) after the 90th Congress (1967-1969). Those Representatives who began their careers in the latter half of the Cold War displayed similar voting patterns on foreign policy to their Midwestern centrist colleagues and the rest of the GOP. When Rep. H.R. Gross (IA-3) retired in 1975, the Old Right and its redoubt in the Midwest went extinct.

While elections alone do not explain this transformation, there is one, in particular, that does appear to have had an outsized impact upon the Midwestern right, the 1964 general election. The GOP was absolutely boat raced in 1964. In addition to the monumental defeat of Barry Goldwater, the Democrats gained supermajorities in both chambers of Congress. Historians often cite Goldwater’s loss as a watershed event for American conservatism. Scholars and pundits have interpreted the defeat as the first salvo in a rightward turn for the country, culminating in Reagan’s election in 1980.

While 1964 may have constituted the birth of the New Right, it spelled the death of the Old Right. The down-ballot drag of Goldwater and his perceived militarism ironically punished the handful of Old Right Republicans who still resisted critical facets of the Cold War. Midwest Republicans lost several pivotal seats held by veteran politicians. The Midwestern Representatives incumbents who were defeated that year were more conservative and more noninterventionist than any regional cohort within the party. Those defeated Midwesterners averaged an opposition percentage of 48% and were considerably more conservative than those Midwesterns who won compared to other Republicans from elsewhere in the party.

| Outcome | Region | Mean Ideology | Mean Opposition | Number | Mean Age | Mean First Congress | Mean Born | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost | Midwest | 0.318 | 0.486766964 | 16 | 57.3125 | 84.1875 | 1906.6875 | 0.228571429 |

| Lost | North | -0.1195 | 0.282690823 | 10 | 55.9 | 84.2 | 1908.1 | 0.23255814 |

| Lost | Rockies | -0.0145 | 0.238602849 | 2 | 54.5 | 82.5 | 1909.5 | 0.5 |

| Lost | South | 0.558 | 0.454636092 | 1 | 36 | 88 | 1928 | 0.083333333 |

| Lost | Southwest | 0.8215 | 0.56346783 | 2 | 38.5 | 86 | 1925.5 | 0.5 |

| Lost | West | -0.033 | 0.32323899 | 4 | 55.75 | 82.25 | 1908.25 | 0.19047619 |

| Won | Midwest | 0.126314815 | 0.359528803 | 54 | 51.7037037 | 84.11111111 | 1912.296296 | 0.771428571 |

| Won | North | -0.357 | 0.220279764 | 33 | 52.15151515 | 84 | 1911.848485 | 0.76744186 |

| Won | Rockies | 0.2825 | 0.49007687 | 2 | 38.5 | 87.5 | 1925.5 | 0.5 |

| Won | South | 0.200909091 | 0.339201965 | 11 | 44.54545455 | 85.90909091 | 1919.454545 | 0.916666667 |

| Won | Southwest | 0.32 | 0.334488773 | 2 | 56.5 | 82.5 | 1907.5 | 0.5 |

| Won | West | 0.074117647 | 0.273109093 | 17 | 54.41176471 | 83.76470588 | 1909.588235 | 0.80952381 |

The election also served as the last mechanism of a generational turnover for the GOP and its rightwing. The mean age of Southern Republicans who won was 44, Midwesterners who lost, 57. Not surprisingly, the mean first Congress for the Midwesterners was the 84th (1955-1957), for Southerners who won, the 88th (1963-1965). Goldwater did not appear to impact the down-ballot races within the Southern states. The small but sturdy Southern Republican cohort largely defended their seats (91% of incumbents won). Southern Republicans also picked up seven new House seats. The combination of incumbent wins and new members accelerated the ascent of a younger New Right. The center of gravity for the Republican right quickly swung towards the South and the West and thereby homogenized the party’s foreign policy vision for the end of the Cold War.

When comparing the evolution of the Midwest to the rest of the party, it becomes apparent that what regional differences exited within the Republican party were firmly erased by the end of the Vietnam War. The Midwestern Republicans, on average, tacked firmly to the center. The average Southwestern, Western, and Southern Republican firmly tacked the right. However, by the Reagan revolution, ideology and geography were irreverent to Republicans’ foreign policy perspectives. They’re all interventionists now…save for this man, of course

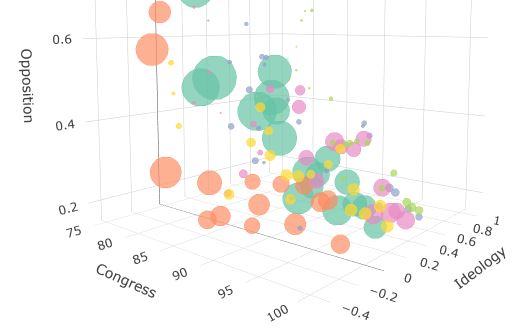

This interactive graphic depicts the ideological and foreign policy evolution of the Republican Party and regional cohorts. Each orb represents a region of the GOP. The x-axis depicts Congress, the y-axis is the ideological average (the higher the number the more conservative), and the z-axis depicts each regional cohort’s average opposition to U.S. foreign policy. Each orb is sized by its relative size within the GOP. The Republican Midwest tacked dramatically to the center throughout the Cold War as it opposition steadily dropped.

When compared to some of my other work, this research led me to a hypothesis: the regional, educational, and ideological particularities of the Republican Party were consumed into a national narrative of America in the world by media and political centralization. The new nationalized Republican narrative closely resembled that of the Old Left, albeit with some of the trappings of the Old Right, particularly a penchant for unilateralism. By the end of the Cold War, this process eliminated significant dissent on U.S. foreign policy and set the stage for a (nearly) unquestioned transition into an American unipolar empire.

After 1989 there were only two flavors of American foreign policy thinking in Washington. Voters could pick from the multilateral* internationalism of the Democrats or the unilateral internationalism of the Republicans. The power elite in Washington and the parties no longer represented distinct ideologies or regional perspectives. Coke or Pepsi, you could choose either, but they were both colas.

As America’s political geographies change again, this time as an urban v. rural divide, right-wing opposition to U.S. foreign policy is nationalizing while conversely centralizing in the country’s rural and exurban communities.

If that sounds a little too tin-foil-haty for you, I’ll leave you with a quote from a scholar, Michal Lind. Lind’s work has focused heavily on the nationalization of American political culture, which is relevant here.

“[T]he real story of the evolution of the American class system in the last half century [is] toward the consolitation of a national ruling class. [R]egional particiates have been absorbed into a single, increasingly homogeneous national oligarchy”

Michael Lind, “The New National American Elite” Tablet, 19 Janurary 2021, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/new-national-american-elite

*Offers of multilateralism are not redeemable for all wars or conflicts. Substantive offers are only redeemable by the governments of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. All other offers are only valid for peacekeeping missions, cushy assignments, or photo ops. Void in the event of serious casualties or domestic backlash. Please consult your parliaments, congresses, or military juntas for details