Recently, I had the pleasure of speaking with Tom Woods on the noninterventionist right and their legacies for the present.

Check it out.

Historian and Writer

Recently, I had the pleasure of speaking with Tom Woods on the noninterventionist right and their legacies for the present.

Check it out.

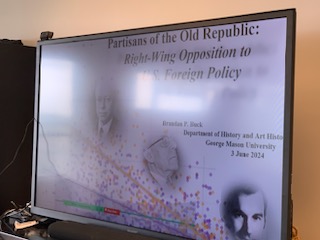

Today, I passed my dissertation defense for “Partisans of the Old Republic: Right-Wing Opposition to U.S. Foreign Policy.” This is the culmination of a years-long journey not just with the PhD but also through the tribulations of the COVID era and the struggles of raising a young son. I couldn’t have done it without the love and patience of my dear wife and family. I look forward to finishing this up as a book and future projects!

Recently, I had the pleasure of speaking with the great Kelley Vlahos on her new show, Trip the Beltway Fantastic Podcast, about the information state, past and present. Give it a listen!

Recently, I appeared on Security Dilemma, a podcast of the John Quincy Adams Society, to discuss the foreign policy views of the Old Right and the parallels to today’s foreign policy dissent on the Right. Give it a listen.

Reason was kind enough to allow me to review Did It Happen Here?: Perspectives on Fascism and America, an essay anthology edited by Wesleyan historian Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins. Check it out:

Leftists Debate Whether America Is Fascist in ‘Did It Happen Here?’ (reason.com)

The Libertarian Institute published my latest book review critique of Jacob Heilbrunn’s America Last. Beyond its stated goal, which was at best a mixed bag, Heilbrunn’s tome also attempts to rehabilitate a painfully orthodox interpretation of American foreign policy and its liberal internationalist underpinnings. Much like David Frum’s recent attempt to “uncancel” Woodrow Wilson, Heilbrunn’s book attempts to breathe new life into a beleaguered liberal consensus by offering an often ahistoric and blinkered view of the past.

History Last, Polemics First: A Critical Review of Jacob Heilbrunn’s ‘America Last’ | The Libertarian Institute

As the meme says, it’s all so tiresome, needing to refute the latest hackneyed WWII analogy-based think piece the blob churns out. But, do it, we must. As always, a thank you to the great Libertarian Institute for running my latest, “Neocon Charlie Sykes’ Tortured Analogies, Past and Present,” linked below.

Neocon Charlie Sykes’ Tortured Analogies, Past and Present | The Libertarian Institute

I’m pleased to share that Responsible Statecraft published my latest article on the historical debates about the U.S. commitment to NATO and European security. It argues that the reciprocal outrage of Trump’s comments and the ensuing media response has obscured long-standing historical debates about Americans’ relationship to the Old World. Give it a read:

Beyond the Noise: NATO Debates, Past and Present | Responsible Statecraft

This isn’t a personal blog, but today, my family had to say goodbye to our long-time pet, Kilroy, a retired racing greyhound. We had him for almost ten years, and his life here with us was firmly intertwined with my life in graduate school. So, writing about him here seems appropriate.

Two of those years were during a long bout of unemployment, which, as you may imagine, was a difficult time in our lives, especially mine. Having him around the house to keep me company and to keep me occupied was a lifesaver. Otherwise, especially in those early years, in which my novelty had yet to wear off, he was my “study buddy.” He would lie next to me as I spent hours reading, rolling over on occasion to solicit a “walkies” break.

On the bright side, my mother now has someone to dote on. My mother died six years ago. During our first visit to my parent’s condo after her passing, Kilroy paced around their place whining, in obvious distress, looking for where she had gone. When he realized she was gone, Kilroy went into my parent’s room, which he never did, laid by her side of the bed, and let out a mournful sigh.

It was the most wretched yet beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.

This morning, when we knew it was time, we sat with him and gave him ample hugs and a “pup cup” from Starbucks. I made him bacon and eggs for breakfast. He loved that.

His last walk was difficult but dignified.

He went peacefully.

I am pleased to share that today, I made a panel appearance at the Cato Institute with Dr. Victoria Coates, moderated by Justin Logan, Director of Defense and Foreign Policy Studies. We discussed the current discord within the Republican Party’s positions on foreign policy, its past (my department), and what might come next.

In case you missed it, watch at either of the links below:

View on the Cato website: Old Right, New Right? What History Suggests about the Future of GOP Foreign Policy | Cato Institute

View on C-SPAN: Republican Party Foreign Policy Priorities | C-SPAN.org