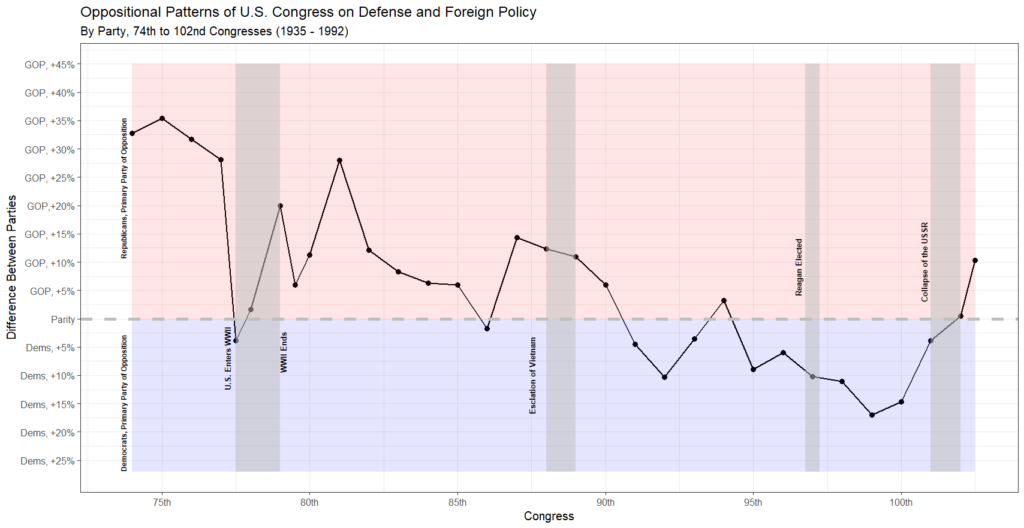

Below is an animation that depicts congressional voting patterns on foreign policy from 1935 until 1992. The data is faceted by party, Democrats on the left, Republicans on the right. Each dot represents a congressperson or senator, as indicated by shape. Each member is colorized by the region from which they hailed. Each member is situated by their position on a two-dimensional left-liberal – right-conservative political spectrum (x-axis). Each member is also situated on a y-axis that depicts their level of opposition in any given Congress, shown in the graphics title portion.

See the full-screen version here.

During the early interwar period (74th to 76th Congresses), the Republican party displayed higher opposition to American involvement in growing hostilities on the European continent. However, despite these patterns, plenty of Democrats across the political spectrum voted along a noninterventionist line. Particularly on the issue of intervention in the Spanish Civil War, both parties were in virtual agreement in both chambers of Congress.

However, with the threat of hostilities between Hitler and the western allies, Democratic and left-wing / Northern Republican opposition to U.S. policy fell rapidly. The Overton Window on American involvement in Europe’s war narrowed as Hitler’s forces goosestepped across the continent. On the eve of Pearl Harbor, only the rightwing of the Republican party, particularly its Midwestern cohort, posted significant opposition.

After the Allied victory in World War II (1945), domestic opinion on America’s role in the world began to take shape. Of all political factions in Congress, Northern and moderate Republicans were the most changed by the war. What few stragglers remained within these pockets of the GOP were converted by the Korean War when it became apparent that confrontation with the Soviets was here to stay. These Republicans joined an almost unanimous Democratic support for the Cold War and formed the power Cold War consensus animated U.S. policy throughout the conflict.

Despite this powerful consensus, resistance to the Cold War status quo remained in pockets of the far-right, particularly within the GOP’s rural Midwestern contingent. These holdouts adhered to conservative and libertarian critiques of the mass state and opposed critical facets of the confrontation. Among their points of dissent were:

- Foreign aid.

- U.S. involvement in multilateral security agreements like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

- U.S. involvement in supranational organizations like the United Nations.

- The overseas deployment of American troops.

These contours of dissent remained the norm during the early Cold War (79th until 90th Congresses, 1945-1969) until they were finally evaporated due to generational turnover within the Republican party and political realignment due to the Vietnam War.

In the wake of Vietnam, the contours of American attitudes when into turmoil. The growing New Right dissented to Nixon’s recognition of China but warmed to specific initiatives like covert aid in the Angolan Civil War. From the late 1960s onward, the right of the GOP became increasingly less Midwestern and more Southern. This shift from “flyover country” to the “gunbelt” solidified the homogenization of conservative thinking on foreign policy for the rest of the Cold War. Meanwhile, the Democratic party became the primary party of the opposition when a younger generation of Democrats was inspired by the excesses of the Vietnam War channeled their frustrations into other aspects of the Cold War.

During the Reagan era (97th to 101st Congresses), the poles of opposition remained flipped. The Democratic party, particularly with its left-wing and some left-wing Republicans, offered stiff resistance to certain defense spending items and aid to militias in Latin America.

By 1991-1992 (101st to 102nd Congresses), the parties and their various segments settled into the same range of opposition. While there were a few outliers and points of disagreement on specific interventions, significant differences in ideology, party, and region evaporated when the U.S. entered unipolar hegemony. This homogenization of foreign policy thinking solidified concepts of America’s role in the world and set the stage for the muscular response to 9/11 and the reignition of hostilities with the Russian federation.