Rather than polish off my first dissertation draft (as a disciplined person might) I have spent the last couple of days running down some data rabbit holes. Because some days you just don’t have your fastball (writing) and you’ve got to lean on your change-up (computation)…or at least that’s what I’ve been telling myself.

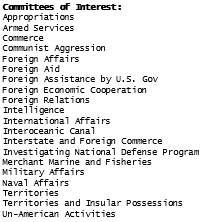

I’ve been digging into the “Database of [United States] Congressional Historical Statistics, 1789-1989 (ICPSR 3371).” Among its datasets is a roster of House and Senate committee membership. Using this data, I am curious if I can glean any insights into the Republican party’s transformation into interventionism in the wake of the Second World War. There are a number of committees related to America’s role in the world. I compiled a list of these committees (see below), extracted the membership data, and compared it to the ideological data from VoteView’s dataset.

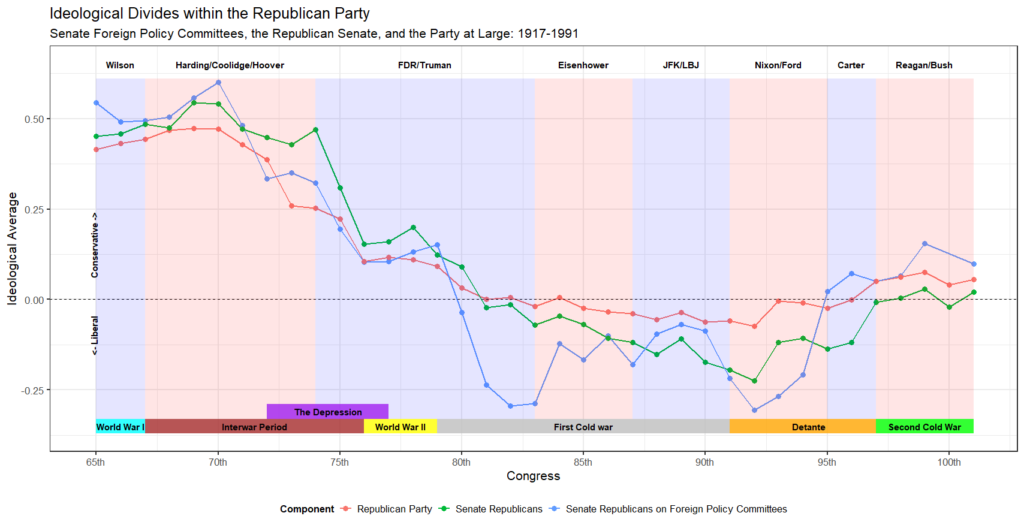

In the upside-down world of the Old Right, conservatism was highly correlated with noninterventionism. During the interwar period, WWII, and the nascent Cold War, the more conservative a Republican, the more likely they were to be a noninterventionist. Conversely, America’s push into World War II, the early Cold War, and the national security state was a largely Democratic, liberal Republican, and internationalist political project.

However, the GOP tacked to the center throughout much of the early 20th Century. The party only began to tack back to the right on the eve of the Reagan Revolution. Yet this return to the right was fueled by the New Right, which held fundamentally different views of America in the world.

The Republican cohort within the Senate was also noticeably more conservative than the party from 1917 until 1949. However, until the Nixon era, Republicans in the Senate were significantly more liberal than the party writ large.

This divide is even starker within Republican representation in the various Senate foreign policy committees. The ideological composition of those members was dramatically more liberal during the formative years of the Cold War orthodoxy (79th to 85th Congress, 1945 to 1957).

What might account for this? 16 Republicans who had an oppositional voting record on foreign policy (voted in opposition more than 50% during their careers) and who served on one or more of these committees left office during this period. Only five of them did so via electoral or primary defeat. The rest either retired or died in office; eight left Congress via the morgue and not the ballot box. All but two of them were right-of-center.

| Name | Career Oppo % | Ideological Score | Reason for Leaving Congress | Region | |

| 1 | CAPPER, Arthur | 0.6649215 | 0.812 | Either did not seek reelection, retired, or not a candidate | Midwest |

| 2 | ROBERTSON, Edward Vivian | 0.6122449 | 0.772 | Defeated in general | Rockies |

| 3 | WILSON, George Allison | 0.6086957 | 0.589 | Defeated in general | Midwest |

| 4 | TOBEY, Charles William | 0.5051546 | -0.632 | Died in office | North |

| 5 | TAFT, Robert Alphonso | 0.5741627 | -0.328 | Died in office | Midwest |

| 6 | JOHNSON, Hiram Warren | 0.7323944 | 1.008 | Died in office | West |

| 7 | THOMAS, John | 0.6568627 | 0.839 | Died in office | Rockies |

| 8 | SHIPSTEAD, Henrik | 0.7716049 | 1.188 | Was not renominated or lost in the primary | Midwest |

| 9 | BROOKS, Charles Wayland | 0.5773196 | 0.388 | Defeated in general | Midwest |

| 10 | BUSHFIELD, Harlan John | 0.7234043 | 0.950 | Died in office | Midwest |

| 11 | HAWKES, Albert Wahl | 0.5818182 | 0.370 | Either did not seek reelection, retired, or not a candidate | North |

| 12 | WILLIS, Raymond Eugene | 0.6625000 | 0.412 | Either did not seek reelection, retired, or not a candidate | Midwest |

| 13 | BUTLER, Hugh Alfred | 0.6503497 | 0.624 | Died in office | Midwest |

| 14 | REED, Clyde Martin | 0.5681818 | 0.356 | Died in office | Midwest |

| 15 | WHERRY, Kenneth Spicer | 0.7065217 | 0.765 | Died in office | Midwest |

| 16 | LA FOLLETTE, Robert Marion, Jr. | 0.6428571 | 0.998 | Was not renominated or lost in the primary | Midwest |

From my research, only one of those who died in office was succeeded (either by appointment or replacement) by a like-minded interventionist. And, as in the case of “Mr. Republican” Sen. Robert A. Taft, was replaced by a liberal Democrat, Thomas A. Burke. Sen. Burke’s career was short-lived, but he did however in effect cast the deciding vote in the failed Bricker Amendment. However important his vote on the Bricker Amendment, Burke’s time in the Senate was short-lived as he was defeated by a moderate Republican and interventionist convert, George H. Bender

Was there was a conspiracy to replace these departed “isolationists” with more liberally minded internationalists? I cannot tell; however, in some sources I’ve encountered, the foreign policy views of potential replacements were discussed by Republican governors or gubernatorial candidates who would have been in a position to replace them. And indeed, the mood of the national Republican party by 1948 (and definitely by 1953) was one of interventionism; this may have impacted the processes of appointment.

All of this is to say that the Republican right’s turn towards militarism and interventionism was not a fait accompli dictated by events, nor was it the outcome of materialist causes. It resulted from human action in intraparty politics, coupled with some well-timed happenstance.