While researching chapter four of my dissertation, “Partisans of the Old Republic,” I stumbled upon a speech given by Representative Ronald Brooks Cameron (D-CA), entitled Who is Doing the Devil’s Work in American Politics?” on 20 May 1963. In his address, Cameron he lambasted the John Birch Society and its influence on conservative politics. His use of rhetoric, guilt by association, arguments from hypotheticals, and hyperbole is a useful window into the era’s crazed political climate and a useful tool for understanding our own political inanities.

A copy of Cameron’s speech within the Congressional Record can be found on the congress.gov website, and I uploaded a copy here.

The Birchers became a tool of political rhetoric and discipline, one used to limit the Overton Window and rein in the then-growing conservative movement. In a speech on the floor of the House of Representatives, Cameron[i] used the specter of the far-right to assail the John Birch Society and other conservative organizations and individuals within its orbit. Cameron’s speech, “Who is Doing the Devil’s Work in American Politics?” sought to tie the already controversial Birchers to the openly antisemitic Gerald L. K. Smith and his periodical Cross and the Flag. Cameron then used the fear of these two groups to question the legitimacy of the emerging conservative movement, declaring, “[w]e are all aware that democracy is under attack by the radical right.” After warning about the fate of democracy, he prefaced his accusations with a reminder of Robert Welch’s more outlandish claims; among them, President Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles were agents of the international communist conspiracy. Cameron further warned that the members of the society had already “infiltrated” Congress.

As with the America First Committee three decades earlier, Cameron highlighted and amplified the tenuous connection between these two camps of the right and then used the proximity of other conservative figures to the John Birch Society to control the Overton Window. His evidence of such a connection was Smith’s professed affinity for the John Birch Society due to its staunch anti-communism. He quoted Smith as declaring that “[f]ollowers of mine who have access to our literature should attend the John Birch Society meetings in their community.” However, Cameron noted that Smith complained that the society did not center its conspiracism on antisemitism. Cameron quoted Smith as lamenting that the Birchers “not only do not discuss the Jewish issue but once in a while they are tempted to bite a little flesh out of some of us who have dared to discuss the Jewish issue.”

Despite Welch’s refusal to cross the line of open antisemitism, Cameron nevertheless saw these connections as profoundly troubling. He declared that “[t]hus we have evidence that the parasites of religious and racial prejudice are crawling into bed with the John Birch Society”. He added, “I shudder to think of the hideous offspring of such a mating.”

With the toxicity of the John Birch Society magnified, Cameron warned that society continued to use its influence to shape policy and governance. Cameron’s target of choice was the Americans for Constitutional Action (ACA) and their access to members of Congress. He asserted that half of the ACA leadership were members of the John Birch Society and that the ACA maintained numerous other financial connections with the society. He stated that the ACA attached itself “like a political leech” to Congress and could “transfer the image of respectable conservatism to radical rightwing extremism.” Throughout the rest of his speech, he called out the identities of alleged Birchers, including several prominent Old Right noninterventionists and members of the Citizen’s Foreign Aid Committee (CFAC). Among the names mentioned by Cameron were the “enthusiastic Bircher,” former congressman Howard Buffet and CFAC member General Bonner Fellers. He also noted that the ACA distributed materials from the “reactionary” Dan Smoot.

To cap off his speech, Cameron invoked the recent history of Europe’s experiences with totalitarianism. He warned that while the danger of such organizations was minimal during regular times, he caveated this by asserting Americans were enduring an environment perilously close to those which ushered in communism and Nazism. For him, the Cold War constituted “a crisis” that could empower those with “extremist panaceas [to] become a real threat to democracy.” While Cameron did not explicitly claim that groups like the John Birch Society were plotting a fascist takeover of the U.S., his speech did much to connect their” extremism” and the eventual destruction of the American way of life.

Cameron’s speech was proliferated by the Associated Press and republished in local newspapers in his home state of California and throughout the country. The speech was also reprinted via the Congressional Printing office and distributed by Birch-watchers. A copy of Cameron’s address is located in the papers of Bryan W. Stevens, a noted Birch reporter; it was in Stevens’s papers where I initially encountered the speech.

Its destination serves as proof of its intent to serve as a means of political propaganda. To be fair, the printed congressional speech was a typical political messaging tactic in the days before the internet, one that the right also engaged in. The scheme often worked one of two ways. First, a political figure would deliver an address, sometimes in conjunction with an outside, nominally independent political organization. Then, said the organization would pay to print copies of the speech (portions of the Congressional Record could not be printed at taxpayer expense). Printed copies would then be circulated through mailing lists, handed out at events, etc. Conversely, political groups would often write ideologically aligned congressional members and ask them to enter a written item into the Congressional Record and then provide the funds to print it.

Either way, the relationship added a veneer of state authority to a partisan political goal. And such is the case with Cameron’s speech, with its title “Who is Doing the Devil’s Work in American Politics?” emblazoned upon an official government document (see below).

Page one of the printed version of Rep. Cameron’s address. Note the provocative title prominently depicted beneath the authoritative congressional masthead. Source: Stevens, Bryan W. The John Birch Society in California politics, 1966: by Bryan W. Stevens. The Publius Society, c 1966. Political Extremism and

Radicalism, link.gale.com/apps/doc/RAICBF251389805/PLEX?u=viva_gmu&sid=bookmark-PLEX&xid=370d8729&pg=183. Accessed 3 Feb.

2022

And what was the political goal? To use the John Birch Society (JBS) as a bludgeon to be used against the conservative movement writ large. By 1963, the JBS was clearly serving that function for Cold War liberals and progressives. And to be fair, the society and its leader, Robert B. Welch, did not do themselves many favors. From Welch’s insinuation that Eisenhower was a commie, to their generous use of the “communist” label, to some of their more outlandish conspiracist claims, the JBS and Welch gave their detractors plenty of rope to hang themselves with. However, despite these angles of attack, the group’s eccentricities were not enough to make them uniquely toxic.

Despite the labels applied to them, the Birchers embodied a then-declining bourgeois Americanist social order at odds with the ascending postwar managerial state. The society was considerably more antielite and often antistatist than attacks leveled upon them would otherwise suggest. They similarly embraced a view of economic relations and a conspiratorial view of history that, while in 1963 was considered “extreme,” would have seemed banal or downright ordinary 30 years prior. And thus, as during the First Brown Scare, the JBS’ ideological proximity to other, more objectively and explicitly illiberal or antisemitic organizations was used by their opponents to achieve their political ends. The group’s real and imagined proximity to odious actors like Gerald L. K. Smith became essential for the political attacks against them. Despite the admitted distance between Smith and Welch, their shared anti-elitism and the occasional rightward drift of some former Birchers was enough to rope the two groups together.

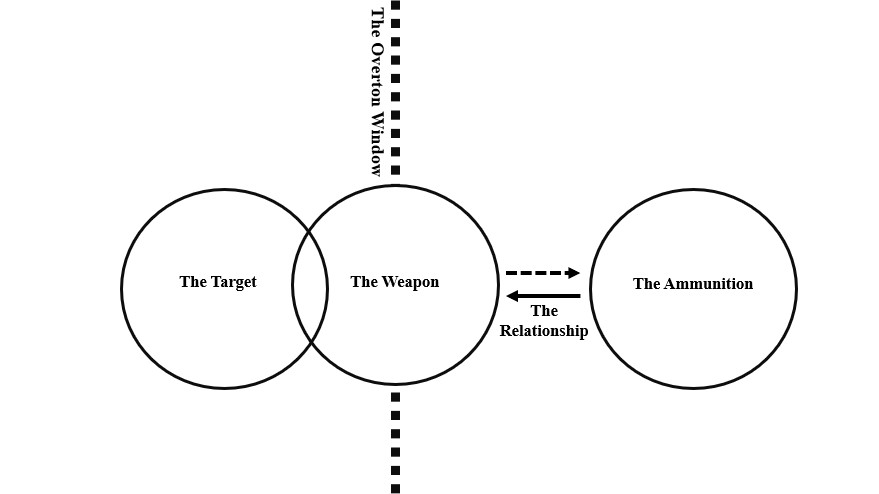

In this formulation, we see one example of a common adjacency attack meant to shrink the political coalition of one’s political opponents. In 1963, Smith and his publication had no political clout. However, the Birchers did. Therefore, Smith and co. became the ammunition used to make the JBS even more radioactive than they were on their own. Once completed, the society was then used as a weapon against other political targets further inside the Overton Window. Conservative power brokers like William F. Buckley then furthered the process along and exiled the society and, as a result, aided liberals in moving the Overton Window ever leftward (see my crude graphic below).

This graphic depicts the relationship between different ideological parties as it relates to an outside political force and their attempts to control the political discourse of their opponents. The “weapon,” in this case, the John Birch Society, stood astride the rightward edge of the Overton Window. Their opponents used their proximity, real and exaggerated, to make them a radioactive bludgeon, which could then be used to discipline “the Target,” the rest of the political right.

This three-degree tactic is, of course, not limited to the left. The right, for a time during the McCarthy era, used the same approach to varying degrees of success, and indeed even the Birchers themselves tried to do the same to their opponents. The difference, however, is that after the inglorious end to the career of Tail gunner Joe, McCarthyite became a slur; no such pejorative exists to describe the reverse. “Cameronite” isn’t a thing.

And it isn’t a thing because the Birchers and other targets of the Second Brown Scare are not traditionally treated as sympathetic characters due to their opposition to key components of the modern liberal program, chiefly Civil Rights. Despite a brief period of nuance in the 1990s and early 2000s, the historiography of these events has reverted back to a narrative largely resembling that of Cameron’s speech. The double whammy of Brexit and Trump has provided incentives to justify current moral and political panics but resuscitate those of yesteryear.

[i] According to the data analysis I have conducted for this project, Rep Cameron’s opposition rate to U.S. foreign policy during his four-year congressional career (1963-1967) was a mere 7%, a statistic of note given Cameron’s politics and political targets.