I thought I’d take a detour from writing chapter one to craft a quick blog post on something which has been wracking my brain, how did the American experience in World War I impact “isolationism” on the eve of World War II? Of course, historians of noninterventionism have covered this topic, and I’ve touched on it myself. However, I am curious to see if this relationship was reflected in my dataset. Comparing the voting habits of those members who served during the 65th Congress (1915-1917) and the 77th Congress (1941-1943) revealed some interesting trends.

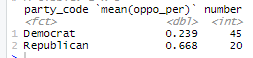

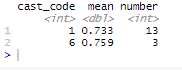

Looking at Voteview.com’s dataset, 20 Republicans who served in Congress, either in the House or the Senate, on the eve of U.S. entry into WWI and voted on the declaration of war with the German Empire were also in Congress as the U.S. entered WWII. Those 20 Republicans averaged 66% opposition to U.S. policy on the eve of WWII, whereas the 45 Democrats who served during both eras averaged just 25% opposition.

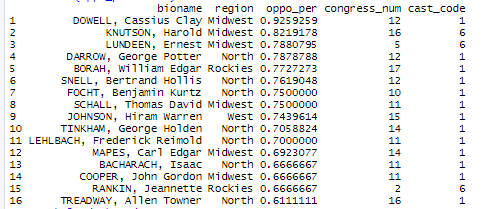

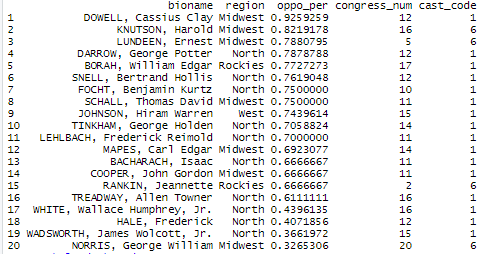

Only four of those 20 posted opposition percentages less than 60%, Allen T. Treadway (MA), Wallace White (ME), Fredrick Hale (ME), James Wadsworth Jr. (NY), and George Norris (NE)

Norris, the New Deal-supporting Republican, turned Independent, was the only member of the 20 who opposed U.S. entry into WWI but became a reliable supporter of U.S. policy entering WWII.

The remaining 16 posted opposition percentages between 61% and 92% to U.S. foreign policy between the 74th and 77th Congresses (before Pearl Harbor). Interestingly, when grouped by their position on entry into WWI, they posted similar opposition to the run-up to WWII. William Borah, “the Great Opposer,” was perhaps the most well know of the 14 and became known for his passionate opposition to the future involvement of the U.S. in foreign wars. And, for those who do not know, only Jeannette Rankin of Montana opposed U.S. entry into WWI and the declaration of war upon Japan after Pearl Harbor.

The Great War and its aftermath solidified Republican opposition toward entry into the Second World War. Whether or not that was “good” or “bad” is irrelevant. “Isolationists” were not merely motivated by myopia, nativism, or antisemitism. Many, like these congresspeople, looked back upon American entry into the Great War and vowed not to do it again.